Exhibits

Irvington's Golden Age of Ghouls

One of our permanent exhibits at the Bona Thompson Memorial Center focuses on Irvington’s seamier side, namely the Ghouls of Irvington. Currently, there are three main topics on display.

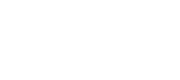

Dr. H. H. Holmes

For over a decade, Al Hunter has led haunted tours through Irvington. One evening in 2004, after telling the story of the Irvington murder of 10-year-old Howard Pitezel by H.H. Holmes, America’s first serial killer, an elderly couple approached him and said that they had a collection of materials related to Holmes which they “just wanted it gone.” Hunter said he was interested, and would talk to them after the tour ended, but by that time the couple was gone, and he forgot all about it.

The following week, as Hunter was leading another tour, an elderly couple approached Hunter’s wife, Rhonda, with a box, saying only, “This is for Al. He is expecting these.” She thanked them and accepted the box assuming her husband knew all about it. When she showed him the box, she learned that he had never gotten their names, so they were never able to reconnect with the couple. The only clues that they left behind were the comments that they had attended one of his tours in Greenfield and that the objects had “belonged to a relative.”

The collection contains a variety of items, including a number of relics that are easily connected to H.H. Holmes. While the exact history of these objects remains a mystery, a selection of the items is on display at the Bona Thompson Center.

Madge Oberholtzer & D.C. Stephenson

On January 12, 1925, the 29-year-old Madge Oberholtzer met her Irvington neighbor, D.C. Stephenson, for the first time while she was volunteering at a political event. Stephenson had just been named the Grand Dragon of the Indiana Ku Klux Klan and had used his position to help elect a number of state candidates. Stephenson was impressed with Madge and employed her to work with him during the General Assembly session, and to help him write a new textbook for the Indiana schools.

Late on the evening of March 15th, Stephenson telephoned her house saying that he needed to discuss something important with her before he left for Chicago. He asked if she could come down to his house, located just a couple of blocks away. He sent one of his aides to escort her.

Upon her arrival, Madge was coerced into having several alcoholic drinks. Stephenson told her that he wanted her to come with him to Chicago. She was forced into his car with a couple of others and they drove to the Indianapolis Union Station where they boarded the train to Chicago. During the trip, Madge was raped and severely bitten by Stephenson.

They got off the train in Hammond, Indiana where Stephenson checked them into a hotel. The following morning, Madge talked him into letting her go shopping for a hat and some rouge since a proper lady would never be seen in public without either one. While she was out, she bought some very strong poison which she tried to take as soon as she got back to the room. When they realized that she was gravely ill, Stephenson, his aide and a driver put her in a car and drove her back to his house in Irvington. She was finally taken to her home, with the warning to say she had been injured in a traffic accident. Madge survived the poison but died from an infection caused by Stephenson’s bites. Before she died on April 14, Madge described her experience in a dying declaration that was used to convict Stephenson of manslaughter.

Grave Robbing in Irvington

At her home on the northwest comer of Bolton Avenue and East Washington Street; 27-year-old Glendore Gates died from tuberculosis on July 9, 1902. The funeral service was held at the family home, 5798 E. Washington Street, two days later a horse-drawn hearse carried her body to Anderson Cemetery on East 10th Street. She was laid to rest in a grave described as “too nice to disturb.” A month later 41-year-old farmer John Dietz bought a new suit of clothes, a pair of shoes, and a hat, returned to his Irvington home at the southeast corner of Arlington Avenue and the Pennsylvania Railroad. He ate supper with his family and after they had retired, John Dietz took his revolver and killed himself. He was buried in Anderson Cemetery. A third tragic death came to the community on August 28th when 15-year-old African-American Stella Middleton died of typhoid fever at her home at 24 N. Gladstone Avenue, a few blocks west of Irvington. Family and friends gathered from near and far to attend Stella’s services in Anderson Cemetery.

A few days later, a mysterious caller informed Glendore’s family that her body had been taken from her grave and could be found at the Central College of Physicians & Surgeons near Market Street and Senate Avenue. Her family went to the cemetery and found her coffin empty. It was discovered that other graves at Anderson Cemetery showed evidence of tampering, and the police were notified. With a search warrant, and in the company of a constable and family members, Mrs. Middleton went to the College where Dr. Joseph C. Alexander, the demonstrator of anatomy, led them to the basement. Opening the door, the room was dimly lit by a single flickering gas jet, they saw a makeshift table of boards with ends resting atop barrels. On one was the body of a young woman. The lamp was brought close, Mrs. Middleton choked, “It is she. I plaited that hair the day before she died.”

Reports of other grave robbings at other small cemeteries around Marion County soon filled the newspapers as detectives and families made their rounds to the Indianapolis medical colleges. When asked about these reports of missing bodies, Dr. Alexander said, “No questions are asked as to the identity of the persons that deliver the bodies, or the one to whom the money is paid… Many bodies are brought in that are not paid for… We don’t care where they come from.” The police arrested Rufus Cantrell and five other African-Americans for grave robbing. Dr. Alexander and the janitor at the Central College of Physicians & Surgeons were also arrested. Cantrell styled himself “king of the ghouls” and freely admitted to leading the gang in stealing numerous bodies, which Dr. Alexander paid thirty dollars for each corpse delivered “in good condition.”

The revelations of the Cantrell gang and the practices of the Central College of Physicians & Surgeons led the 1903 Indiana General Assembly to enact legislation creating the state anatomical board that was empowered to receive and distribute unclaimed bodies from throughout the state to medical schools. The act was “for the promotion of anatomical science and to prevent grave desecration.”